Spanning five generations of women—teachers, immigrants, dreamers, farmwives, and one chronic note-maker—Margaret L. Young unpacks what’s been handed down through mitochondrial DNA, family recipes, wartime whispers, and broken brooches. These aren’t queens or celebrities; they’re the women who kept the world turning while no one was looking—and who left breadcrumbs in the form of quilts, cookbooks, and scribbled notes in margins.

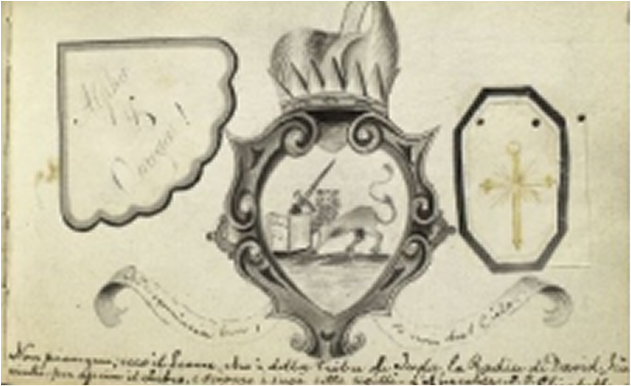

In 15th-century England, clever folks kept common place books—essentially intellectual junk drawers where they jotted down recipes, quotes, letters, poems, and other things they didn’t want to forget (or misplace under the bed). Each one was a reflection of its owner’s obsessions and oddities. By the 16th century, friendship albums blossomed onto the scene—think: proto-yearbooks where your friends would inscribe a witty line, a doodle, or perhaps a cheeky Latin phrase, all upon request. Often born out of European grand tours, these albums became cultural suitcases packed with coats of arms, mini paintings, and souvenirs from local artisans.

Often born out of European grand tours, these albums became cultural suitcases packed with coats of arms, mini paintings, and souvenirs from local artisans. Around 1570, colored plates depicting Enter James Granger, 1775. He printed a history book with bonus blank pages—like Easter eggs for bibliophiles. Readers were encouraged to “extra-illustrate” the book with their own engravings, clippings, and commentary. The practice—later dubbed grangerizing—was essentially Victorian remix culture: cutting up, pasting in, and giving old books a makeover that even Marie Kondo would applaud. Venetian masks or Carnival scenes became the vintage version of album stickers—pasted in not for their narrative power, but because they were simply too fabulous to ignore.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, friendship albums and school scrapbooks gave young women a voice beyond embroidery and polite piano recitals. They chronicled tea parties, heartbreaks, test scores, and dreams. It was legacy-building disguised as craft time. Take a peek at a Smith College scrapbook from 1906 and you’ll find a charming circus of doodles, dried flowers, calling cards, concert tickets, and maybe even a rogue spoon or two. These women didn’t just journal—they curated their lives.

When photography sashayed onto the scene in the 1820s, thanks to Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, it added a new layer of memory-making to scrapbooks. Though photo albums didn’t take off until the 1860s, once the carte de visite became all the rage (think: selfie meets calling card), people couldn’t paste fast enough. Scrapbooks soon became a mashup of images, captions, clippings, and keepsakes. A playbill wasn’t just a program—it was proof that you saw Bernhardt at the theatre. A dried rose? The whisper of a secret admirer. A guest list? Social clout in cursive.

And yes, even Mark Twain got in on the action. Ever the literary packrat, he toted scrapbooks on his travels, pasting in anything that caught his eye (or heart), which basically makes him the forefather of the souvenir hoarder.

Between 1795 and 1834, Anne Wagner—a woman in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s circle— kept a scrapbook that reads like a poetic time capsule. Handwritten verses, locks of hair, ribbon scraps, painted cameos, and heartfelt notes from friends. Her album wasn’t just a book – it was a bouquet of relationships, carefully pressed and preserved.

In sum: scrapbooking is the act of turning life’s ordinary bits into a tapestry of meaning. It’s messy. It’s marvelous. It’s part historical archive, part heart-on-paper. And whether you’re wielding glitter glue or archival tape, it’s still one of the most human things we do—trying to catch time by the tail and paste it down for safekeeping.

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Commonplace book. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commonplace_book

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Scrapbooking. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scrapbooking

Gaskell, P. (1972). A New Introduction to Bibliography. Oxford University Press.

McGill, M. J. (2008). American commonplace: Ephemera and the scrapbook in nineteenth century America. University of Minnesota Press.

Blodgett, E. D. (2002). The scrapbook in American culture. Princeton University Press.

Rosenblum, N. (2007). A world history of photography (4th ed.). Abbeville Press.

Darrah, W. C. (1981). Cartes de visite in nineteenth-century photography. Getty Publications Twain, M. (1877). Mark Twain’s Scrapbook. American Publishing Company.

New York Public Library Digital Collections. (n.d.). Anne Wagner scrapbook, “Memorial of Friendship,” 1795–1834. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https:/digitalcollections.nypl.org/ items/510d47db-b630-a3d9-e040- e00a18064a99

New York Public Library Digital 1 Collections. (n.d.). Anne Wagner scrapbook, “Memorial of Friendship,” 1795–1834. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/ items/510d47db-b630-a3d9-e040- e00a18064a99

Rethinking the Ink

Sheaffer’s Peacock Blue Ink was the color my grandmother used to write letters, both business and social. It was delivered to politicians being admonished, it kept bookkeeping figures, wrote grocery lists, thank you notes—the ink itself had a flair for drama just as her handwriting swooped and dipped like it was doing a waltz in sensible heels. The signature, all loops and curlicues had just enough sauce to keep the margins on their toes.

Peacock Blue A color with a past that dated to before the pharaohs and a personality that still turns heads in a crowded crayon box. It’s a little punchier than your average blue-green, almost like it’s the older, more savvy cousin of Turquoise, but knows how to hold court with both common and king.

Peacock Blue doesn’t whisper, it oozes. It’s the color of beauty with backbone, elegance without ego. It shows up wearing integrity like a life jacket, and reminds you—gracefully, of course—to show your true colors, unapologetically and with flair.

It carries the calming wisdom of the color Blue: serene, supportive, and it is never one to start a scene. Like a French sauce blend of blues and greens; it demands luxury and bathes in taste.

The color Blue is the dependable friend who keeps your secrets, writes your thank-you notes, and brings the snacks to your existential crisis. But here’s where Peacock Blue does more than dance—because it’s also Green. Just enough to infuse a breath of fresh air. Green is the color of health and harmony, of second chances and fresh starts. It’s what you reach for when you need a hug, or a healing, or a hint of good luck tucked in your pocket like a pressed clover.

So when you dip your pen in Peacock Blue, you’re not just choosing a color—you’re calling out confidence and calm, wisdom and growth, all in one elegant swoop. It’s the ink equivalent of knowing precisely who you are and writing it down anyway.

Grandma’s era of personalized stationery included—monograms embossed, borders trimmed in gold, and envelopes that felt like they were making a debut. Cards and letters crisscrossed the country, not always with wings, but always with flair. Back then, the mail had moxie. A birthday card wasn’t just a formality—it was a full-on performance, complete with underlines for emphasis and rogue hearts and kisses if Grandma was feeling nostalgic.

Even the desk on which she wrote had a certain gravitas. It wasn’t just a desk—it was a Writing Bureau. Mahogany or maybe oak, but certainly some kind of handsomely brooding wood with just the right amount of age and swagger. The type of piece that doesn’t just take up room it serves as a compliment to it.

It was a perfect arbitrator for a message written in Peacock Blue. Inside, it was a marvel of compartments—cubbies for letters, skinny drawers for secrets, and a central cabinet with a hidden compartment that practically dared you to find it. The whole thing rose on short feet, like it knew it had something important to say. The dovetailed drawers slid out with a whisper in the winter and with hesitation in the summer, and the original brass batwing handles had the kind of patina that only comes from decades of use and just a hint of rumor.

It was the kind of desk that encouraged proper posture, thoughtful sentences, and maybe a little harmless gossip. You didn’t just dash off a note at that desk—you composed. You summoned elegance and tucked it into envelopes. You sat down with your thoughts and made something beautiful. All in Peacock Blue, naturally.

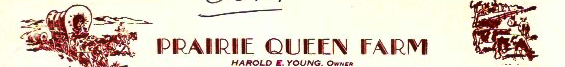

Then there was her self-styled professional stationery. It was more than paper—it was anchored by a bronze stagecoach steadily heading west, a prairie schooner with embossed wheels, pulled by oxen made of Midwestern grit. On the other side of the page was herd of Herefords. The words and wisdom Grandma penned in that bold Peacock Blue ink didn’t just sit there politely—they journeyed across the irrigated pages, leaving wagon ruts of insight and sass in their wake. Each sentence was a trail, each looped descender, a tumbleweed mid-twirl. She wasn’t just writing letters— she was blazing trails from her desk to yours, postage stamp and all. And my grandmother? She was the undisputed queen of the Pony Express.

Her Peacock Blue script practically plunged off the page, turning grocery lists into poetry and thank-you notes into minor works of literature. If ever there was a font with a personality, it was hers—equal parts etiquette and elbow jabs.

Her letters didn’t just arrive—they announced themselves. And when you opened one, you knew: for the next few minutes, you were stepping into her world. A world where Peacock Blue was power, the pen was mightier (and sassier) than the sword, and the mailbox was the original stage door.

Not too long ago, the ink world let out a collective what the heck?—Sheaffer, in a move straight out of the Big Pharma playbook and with all the swagger of Big Ink, decided it was time to mess with a classic and reformulate their beloved Skrip ink. And get this—they outsourced production to Slovenia. Slovenia! I mean, most folks had to dust off an old globe just to figure out where that even is. (Hint: think former Yugoslavia and a whole lot of head-scratching.)

And then came the real heartbreak: more authentic colors began disappearing like manners at a bus stop. Peacock Blue— emerged as bland old Turquoise. It’s like finding out your best friend, aged 70 now wears braces and sensible shoes. Still lovely, just… changed.

Then, the ink well bottle got pitched, next went the cartridges —once intrigingly transparent, with little windows of possibility that you could actually see through—are now slyly translucent. And what used to be a rainbow of choice has been pared down like an airline snack menu.

I really miss the clarity, the confidence, the unapologetic peacock of all that flowed from Grandma’s pen.

Because ink isn’t just ink. It’s Grandma, her memory, it’s her expression, it’s the personality she bottled and sent out into the world, one envelope at a time. And when it was just right, it sang across the page in a voice only she could write.

I miss seeing the Peacock Blue in my mailbox.

12834 Cheverly Drive

704-575-0917

©Copyright 2025 MARGARET YOUNG. All Rights Reserved.